Day Two - Confession and Reconciliation

Week 6

This is the audio recording of the second reading of week eight of Start, entitled Confession and Reconciliation.

“Few things accelerate the peace process as much as humbly admitting our own wrongdoing and asking forgiveness.”

In this week’s first reading, we said that it is through receiving forgiveness from God that we can best grow in our ability to forgive one another. Today, we will examine two practices integral to forgiveness: confession and reconciliation.

What comes to mind when you think about confession? For some, it may evoke images of a small dark room where sins are confessed to a priest or religious leader. Perhaps you think of a criminal committing a crime or an environment where someone was coerced or intimidated into admitting wrongdoing. It’s fair to say the idea of confession has no shortage of negativity around it.

This negativity primarily exists because the concept of confession has been misunderstood and misused. But it doesn’t have to be that way. Confession, understood rightly, is a gift from God. In James 5:16, James, the brother of Jesus, tells us, “Confess your sins one to another and pray for one another, that you may be healed.” He draws a direct link between confession and healing. Confession, therefore, doesn’t need to be something shrouded in shame and condemnation. Instead, it can be a vehicle God uses to bring about freedom and restoration.1

The purpose of confession is not to dwell on our guilt. Our guilt and shame increase when we hide our sin in the dark. Through confession, we bring our sin into the light to experience grace, forgiveness, and healing. 1 John 1:9 teaches, “If we confess our sins, He is faithful and just to forgive us our sins and to cleanse us from all unrighteousness.” When we bring our sins to God, His response is forgiveness. Therefore, our sins and failures need not drive us away from God. Instead, they can draw us closer because He meets us in our sin with His grace.

Another benefit of confession is that it is a guardrail against pride or arrogance. It is easy to judge the sins of others when we are unreflective about our own. When we take time to acknowledge and confess our sins to God and others, it helps us respond to the sins of others with empathy and kindness. For these reasons and more, it is actually beneficial for us to consider our own sins. Real forgiveness requires truth-telling. So long as the truth is concealed, true forgiveness will not be possible.

Sin falls into two categories: sins of commission and sins of omission.

When we do something we ought not to do, that is a sin of commission. For example, if we lie to protect our reputation, that is a sin of commission. When we do not do something we ought to do, that is a sin of omission. For example, if lies tarnish a co-worker’s reputation and we choose to remain silent rather than come to their defense, that is a sin of omission.

As we process our sin, we must differentiate between three different emotions that can come to mind:

- Guilt includes feelings of regret, worry, or sadness. It is the awareness that we deserve some sort of blame or condemnation for our perceived offense.

- Shame takes guilt a step further. If guilt tells us, “I’ve done something bad,” shame tells us, “I am bad.” In other words, guilt is about what we have done; shame is about who we are.

- Conviction occurs when we are convinced that we have done something wrong or sinful. It includes feelings of sorrow for what we have done and a desire to make things right.

In 2 Corinthians 7, Paul talks about the feeling of conviction his readers experienced when they read his letter. He uses the word “grief” to describe what we might call ‘guilt’ or ‘conviction.’ He writes, “For even if I made you grieve with my letter, I do not regret it—though I did regret it, for I see that that letter grieved you, though only for a while. As it is, I rejoice, not because you were grieved, but because you were grieved into repenting. For you felt a godly grief, so that you suffered no loss through us. For godly grief produces a repentance that leads to salvation without regret, whereas worldly grief produces death.” (2 Corinthians 7:8-10, emphasis added)

Paul highlights the benefit of guilt and conviction: it leads us to repentance. It guides us to a place where we want to repent. To repent means to change our minds. So, godly grief brings us to that point of repentance. Through repentance, we find healing and freedom. Paul contrasts this with worldly grief, which makes us feel bad but doesn’t inspire change. Godly grief can be the beginning of our healing journey, while worldly grief keeps us trapped in self-loathing.

Worldly grief can also cause shame, an extremely harmful emotion. While God may use guilt to lead us toward repentance, shame is never from God. God loves us and recognizes what is good in us, so we can trust that God never wants us to believe we are terrible or unworthy of love.

One of the reasons confession is a gift is that it gives us something healthy to do with our guilt. We do not need to be stuck in denial on the one hand or self-loathing on the other. When we experience guilt and conviction, we can bring that to God and experience forgiveness. And God, in His kindness, invites us to change, and He lovingly walks alongside us in the change process.

We need to consider one final element of confession. As mentioned earlier, James 5 instructs us to confess our sins to one another. But what does that mean? Confession to others serves several purposes. First, if we have wronged someone, confessing our sin to them can start the healing process. Second, confessing our sins to others increases accountability. One well-known pastor says, “Sins we confess only to God we tend to repeat.” For instance, he explains that if two students cheat on their math test, which student is less likely to cheat again: the one who confesses only to God or the one who confesses to both God and their teacher? We might say it shouldn’t be like that—and perhaps that is true — but the reality is, for most of us, confessing to others encourages true repentance more than just confessing to God.

Confession can be awkward and challenging, but when we have the courage to trust God enough to confess to Him and others, we will discover healing and freedom that cannot come if our sin remains hidden. Like almost anything else, confession becomes easier and more natural with practice. The awkwardness fades, and over time we realize that being quick to confess helps us create a safe community that values confession and forgiveness.

Once we have a solid foundation of our own forgiveness and we understand the value of confession, we are better equipped to have these concepts bear fruit in our relationships. We can practice forgiveness and reconciliation so that they become less scary and more normal.

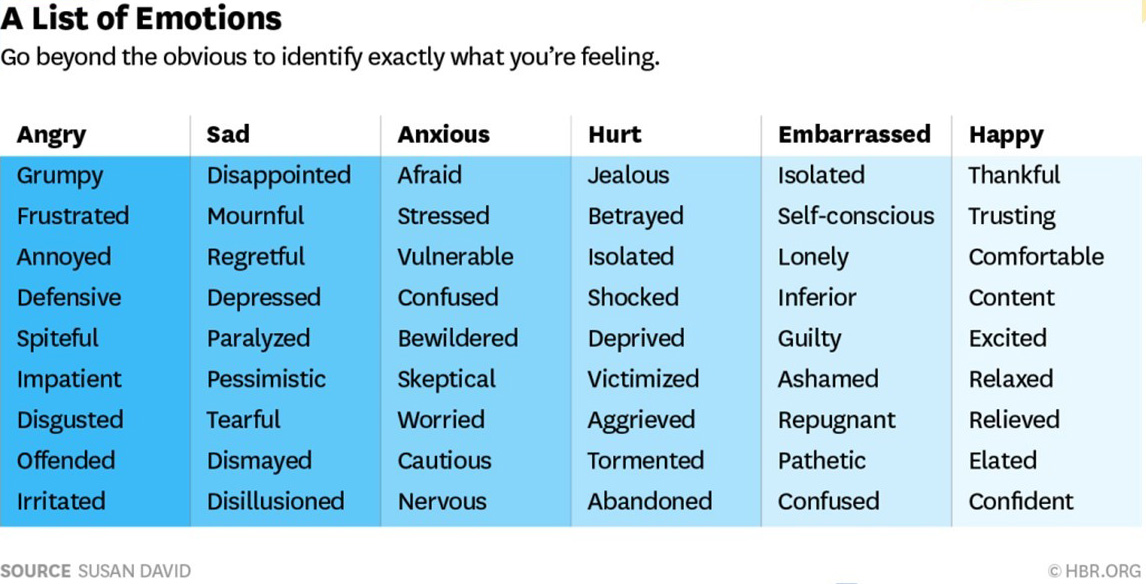

There are two key skills we must develop to practice healthy forgiveness and reconciliation. First, we need to know ourselves well enough to identify and understand our own emotions. Second, we need to know the differences and similarities between forgiveness and reconciliation.

Knowing Ourselves

Real forgiveness is not sweeping things under the rug. It’s not a denial of our emotions or a minimizing of our pain. In fact, if we do those things, we actually limit our ability to give and receive forgiveness. We can’t practice real forgiveness if we are not honest about reality.

How do you know when you’re angry or hurt? Think about that for a moment. Maybe you feel warm, or you can sense your heart rate increase. Perhaps you catch yourself clenching your jaw or grinding your teeth. You may even feel shaky or dizzy. Emotionally, you might become irritable, anxious, or depressed. Anger causes some people to pace, raise their voice, or become overly sarcastic or biting in their communication.

Whatever anger, hurt, or offense looks like for you, it’s hard to address those emotions if you can’t identify them. Just because you don’t recognize them doesn’t mean they aren’t there. In fact, when they are present but unnamed, they can cause the most damage. You’ve probably encountered people who become passive-aggressive, irritable, or generally difficult while refusing to acknowledge that anything is wrong. Unspoken anger and hurt undermine healthy relationships.

When you find yourself becoming angry, you must treat yourself with gentleness and compassion. Many of us have an almost instinctive tendency to judge our emotions, especially our negative ones. This judgment blocks healthy processing. What’s worse, when our ability to process our emotions is blocked, those emotions tend to intensify. Paul instructs us in Ephesians 4 to be angry but not sin, which becomes a much more difficult command to observe when we let our anger build.

Rather than deny or ignore our hurt or anger, a healthier approach is to try to understand them. We can ask ourselves, ‘Why do I feel this way?’ Whatever your answer is, you may find it helpful to ask yourself the seemingly redundant follow-up question, ‘But why?’ Sometimes we must ask ourselves that question a few times before we can get to the root of our hurt.

Because life with other people is messy, it provides ample opportunity for hurt feelings. These feelings are real. One of the most common causes of hurt feelings is real or perceived rejection. Neuroimaging studies have shown that rejection activates the same part of our brain as physical pain. Our hurt can also come from unmet expectations, criticism, a lack of appreciation, or the perception of any of the above. This is why naming our emotions — and sitting with the ‘But why?’ question — is so important. Real forgiveness and reconciliation begin with an honest acknowledgment of what took place and how it affected us.

Take a moment to study this chart from Harvard Business Review. It can be a helpful guide to aid you in identifying the specific emotions you are feeling when you are hurt.

Reconciliation

Forgiveness can be a solo endeavor, but reconciliation requires two parties. Forgiveness means releasing the offender from any payment or debt, and it also frees them from any sort of vengeful response. Reconciliation involves rebuilding trust and restoring the relationship. It doesn’t mean forgetting the offense—in fact, the memory of situations that call for forgiveness can teach everyone involved valuable lessons. However, it does mean that some trust has been regained and all parties have agreed to move forward together.

In past generations, reconciliation was much more necessary than it is now. In an era before social media, unprecedented mobility, population growth, and near-limitless access to new people, people had to reconcile because the limits of technology and mobility required communities to remain in close contact with each other. To be clear, this brought many challenges, but one of the benefits was that relationships were not disposable. There was no such thing as changing churches, ghosting, social media blocking, or any other modern ‘conveniences’ we employ when we wish to discard relationships that become difficult.

In the 21st century, reconciliation is tragically optional. If someone offends us, we can simply end the relationship and move on. In doing so, we deprive ourselves of the relational richness that comes from maintaining friendships over the long haul. Through Christ, we can live a better way. We can practice forgiveness and reconciliation because we have been forgiven and reconciled to God. We can value relationships enough to pursue these things because we know every person was made in the image of God, and God went to great lengths to pursue reconciliation with us. In practicing forgiveness and reconciliation, we set ourselves up to enjoy the richness of deep community, and we model for a watching world the forgiveness and reconciliation that is offered to all of us through Christ.

My Response

- How aware are you of your own sin? Do you tend to err on the side of too much or not enough emphasis on your own shortcomings?

- How comfortable are you observing and reflecting upon your own feelings? Look at the feelings chart and note the words you most regularly use when you’re in distress. What does that tell you?

- Looking at your own life, what has made forgiveness and reconciliation difficult? How have you seen its benefits?

- Take a moment and ask God to search your heart. Think back over the last 24 hours. Think about moments of joy and gratitude, but also think of any sins of commission or omission that come to mind. Consider writing out a list and then confessing those sins specifically and receiving God’s forgiveness. Shred, burn, or crumple up the list once you are done as a physical reminder that God wipes away your sin.

Footnotes

If you have been in environments where confession was abused, or if you have traumatic experiences with this topic, that is something to take seriously. You may want to consider meeting with a counselor to further discuss your experience and pursue healing.